The Tour de France is into its second stage and Lance Armstrong has the yellow jersey on him. He is a great athlete and his story is that of a person that overcomes all kinds of odds and becomes one of the best ever to ride a bike, so far he has three Tour titles under his belt, and he is only two away fro tying the five times record. We can read about it on any sports publication and there is a little coverage about it on the news. What we can not read is about the two fellas that are right behind him, giving him a run for his money. And why is it that nothing is said about these two other competitors?

The Tour de France is into its second stage and Lance Armstrong has the yellow jersey on him. He is a great athlete and his story is that of a person that overcomes all kinds of odds and becomes one of the best ever to ride a bike, so far he has three Tour titles under his belt, and he is only two away fro tying the five times record. We can read about it on any sports publication and there is a little coverage about it on the news. What we can not read is about the two fellas that are right behind him, giving him a run for his money. And why is it that nothing is said about these two other competitors?Well, no one talks about their tiny nation, is taboo in the media to talk about this people unless it serves the purpose of linking them to a terrorist group. Whenever someone from this tiny nation does something great like being on Lance Armstrong's rear wheel on the mountain stage where Lance has no competition, they are called with a different name, the name of the nation that occupies their tiny nation.

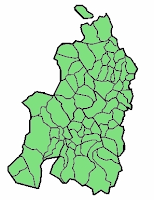

At least yesterday they got to see the green, red and white flag of their followers since for a moment, the Tour de France got close to their tiny nation.

Following the step of their conational, the greatest ever cyclist to run the Tour de France, the one and only Mikel Indurain holder of the five times in a row record, this year it is the boys from Gazteiz, the capital city of the Basque Country. Their names? Joseba Beloki and Igor Gonzalez Galdeano (who by the way donned the yellow jersey for most of the first half of the Tour). No bikes have been harmed or killed in their achievement, so we hope there is no need for people to call them dumb for what they are doing. But you can always count on idiots like this one to attack what they don't understand.

This cheer goes to Joseba Beloki and Igor Gonzalez Galdeano, from the team Once Eroski and their achievements so far in the Tour d' France!

.... ... .