Nafarroa is the largest province of Euskal Herria.

History

During the time of the Roman Empire, the territory of the province was inhabited by the Vascones, a pre-Roman tribe who peopled the southern slopes of the Pyrenees. The Vascones managed to maintain their separate Basque language and traditions even under the Roman rule.

The area was never fully subjugated either by the Visigoths or by the Arabs. In 778, the Basques defeated a Frankish army in the Battle of Orreaga (Roncevaux Pass.) Two generations later, in 824, the chieftain Eneko Arista was chosen King of Pamplona, laying a foundation for the later Kingdom of Navarre. That kingdom reached its zenith during the reign of Santxo III of Navarre and covered the area of the present-day Euskal Herria and Errioxa (La Rioja), together with parts of modern Kantabria (Cantabria), Castile and León, and Aragoia (Aragon).

After Santxo III died, the Kingdom of Navarre was divided between his sons and never fully recovered its importance. The army of Nafarroa fought beside other Christian Iberian kingdoms in the decisive battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212, after which the Muslim presence of more than 800 years on the Iberian Peninsula were slowly reduced to a small territory in the south.

In 1515, the bulk of Nafarroa below the Pyrenees—Upper Nafarroa—was at last defeated after a long war against Castile and Aragon but retained some rights specific to it. The small portion of Nafarroa lying north of the Pyrenees—Lower Nafarroa—later came under French rule when its Huguenot sovereign became King Henri IV of France; with the declaration of the French Republic and execution of Louis XVI, the last King of France and Navarre, the kingdom was merged into a unitary French state.

Community and geography

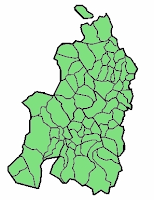

Situated in the northeast of the Iberian peninsula, Nafarroa is bordered by Lapurdi, Nafarroa Beherea and Zuberoa to the north, Aragón to the east, La Rioja to the southwest, Gipuzkoa and Araba to the west. The territory includes an enclave, Petilla de Aragón, which is completely surrounded by Aragón.

It is made up of 272 municipalities and of its total population approximately one-third live in the capital, Iruñea, and one-half in the capital’s metropolitan area. There are no other large municipalities in the region. The next largest are Tudela , Barañain, Burlada, Lizarra, Zizurkil, Tafalla, Atarrabia, and Ansoain.

Despite its relatively small size, Nafarroa features stark contrasts in geography, from the Pyrenees mountain range that dominates the territory to the plains of the Ebro river valley in the south.

Climate

The climate of Nafarroa mixes influences from the Pyrenees mountains and Ebro river valley, creating a great difference between the climates of the north (much more humid and with frequent rainfall) and of the south (more Mediterranean with higher temperatures and more sporadic precipitation). One can pass from the humid Cantabrian valleys in the north to the arid, steppe-like Bardenas Reales on the banks of the Ebro river in just a few kilometers.

Cultural heritage

Nafarroa is a mixture of its ancient Basque tradition and culture with Mediterranean influences coming from the Ebro. The Ebro valley is amenable to wheat, vegetables, wine, and even olive trees as in Aragon and La Rioja. It was a part of the Roman Empire, and in the Middle Ages it became the taifa kingdom of Tudela. In the Middle Ages, Iruñea was a crossroads for Gascons from beyond the Pyrenees and Romance speakers.

Culture

Euskera (Basque) is the official language in Nafarroa, together with Spanish which was imposed through violent means to the indigenous population. The north-western part of the community is largely Basque-speaking while the southern part is almost completely Spanish-speaking. The capital Iruñea is in the mixed region. Nafarroa therefore is divided into three parts linguistically: regions where Basque is widespread (the Basque-speaking area), regions where Basque is present (the mixed region), and regions where Basque is absent (the Spanish-speaking area), a real tragedy for it means the original culture has been wiped out by the invaders.

Since Nafarroa was an independent state in Europe for over 800 years the excuse presented by some scholars insisting that there was never an independent Basque state is not only preposterous but a lie designed to deny the Basque people its right to self determination.

.... ... .

The Tour de France is into its second stage and Lance Armstrong has the yellow jersey on him. He is a great athlete and his story is that of a person that overcomes all kinds of odds and becomes one of the best ever to ride a bike, so far he has three Tour titles under his belt, and he is only two away fro tying the five times record. We can read about it on any sports publication and there is a little coverage about it on the news. What we can not read is about the two fellas that are right behind him, giving him a run for his money. And why is it that nothing is said about these two other competitors?

The Tour de France is into its second stage and Lance Armstrong has the yellow jersey on him. He is a great athlete and his story is that of a person that overcomes all kinds of odds and becomes one of the best ever to ride a bike, so far he has three Tour titles under his belt, and he is only two away fro tying the five times record. We can read about it on any sports publication and there is a little coverage about it on the news. What we can not read is about the two fellas that are right behind him, giving him a run for his money. And why is it that nothing is said about these two other competitors?